When illustrating organizational concepts in client conversations, I used to use the family as an analog. After all, I thought, the family is the smallest organization that most of us are a part of. Then I realized, for some of us, it’s the couple form. Many of the rules of organizational life apply in our most intimate relationships. Then, doing some work with The Google School For Leaders on what Googlers were calling the “system of me,” I began to refer to each of us as complex systems in and of ourselves.

That we are complex systems “containing multitudes” is the premise of much of the work I admire.1 “Human as complex system” captures the logic of the science of sustainable high performance, including the research on the four dimensions of human energy (physical, emotional, mental, and spiritual) work derived from Abraham Maslow’s, developed by sports psychologist Jim Loehr in the context of elite athletes, and elaborated at The Human Performance Institute, and at The Energy Project (where I was a Managing Director, leading an Organizational Transformation Practice and looking after Learning & Development). “Human as complex system” is also an apt caption for transformational leadership approaches based on the “big four” leadership archetypes (Lover, Thinker, Dreamer, Warrior) that Erica Ariel Fox culled from the work of Joseph Campbell and implemented with clients of Mobius Executive Leadership (where I was a Managing Director, rolling out a Winning From Within service line). The Nested Leadership framework (Matryoshka Model) I use with clients also embodies the notion that “we contain multitudes:” the model contains five layers corresponding to human development: 1) who we are at our core, 2) the relational layer we form in connection to others, 3) the developmental layer we inhabit as learners, 4) a professional self accreting over the course of our working life, and 5) a transcendent layer comprising our larger self, bigger than our biggest job.

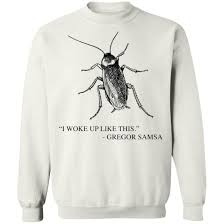

But we can get caught up in ourselves, can’t we? And overlook the way our actions can move others up or down Maslow’s pyramid, satisfying basic human needs, or leaving them unmet. Or disregard the transformational effect we have on others — for good or for ill — as they move along, heroes on their own relational journey. We may relate to one or another of any of the layered leaders of their own lives whom we encounter, either failing to ascertain, or else generously activating, the whole person. In the Matryoshka Model, parts can get (temporarily) lost, or misalign. So we are back to considering (as one of our enterprise clients puts it) — in addition to the “me,” then also the “us,” and for sure, the “it:” in this case, the big “so what” of Kafka’s indelibly memorable piece of writing, and also certainly the big “why” of this series on The Metamorphosis in Close Leaders!

If the first two chapters of The Metamorphosis are about Gregor’s big change, and his own literal navel gazing around it (all those “abdomen” references in the Schocken edition!), the final third of the novella is about the effect of Gregor’s big change on others. The housemaid, terrified, begs to be released from her duties, and quits (89). (Flight risks being a little-discussed side effect of so-called transformational leadership.) Gregor’s sister Grete, who garners little respect from Gregor or their parents at the start of the novella, follows in his footsteps with a twist, taking a job as a salesgirl, and also studying French and stenography in the evenings, so as to elevate herself, now that Gregor can no longer provide for her future. The father who was so indolent at the start of the novella, and so cruel to Gregor upon his transformation (he of the deeply lodged apples: see Post #13 on Identification Out of Fear), has discovered a small but forgotten nest egg, taking some financial pressure of the household for which Gregor has long over-functioned as the sole breadwinner, gotten a job himself (dozing “ready for service” in a “stain-covered jacket resplendent with gold buttons” 87), and curbed his violent ways, seemingly chastened by the damage he has caused to Gregor’s not-inviolable (as it turns out) carapace.

At first it is all just exhausting; the mother falls asleep sewing undergarments for the rich. But something is changing in the family system as its members become more self-reliant, unable to depend any longer on Gregor. Sister Grete moves through her duties of care for Gregor “with a sensitivity that was new in her, one that had now taken hold of the family as a whole” (92). And Gregor, who has undergone as big a change as any leader I’ve ever known, goes one further, in response to the shifts he has prompted. For his part, Gregor, listening to the music his sister pays on her violin for the family’s lodgers of an evening, finally “felt as if he were being shown to that unknown nourishment he craved” (101). In newfound harmony with himself and others, Gregor has reached, unwittingly — despite it all in a feat of what we now recognize as post-traumatic growth — the spiritual peak of Maslow’s pyramid.

And then, just as they achieve these heights, climbing out from the messy middle of the U-curve of this familiar tale, all is in disarray again. The lodgers catch sight of the bug amongst them and give notice. Sis Grete gives up and declares that Gregor has got to go. Gregor agrees, acknowledging how he has begun to weaken and fade away.

In his former bed chamber that has becomes a repository for unused things the family has discarded (a symbol, perhaps, of their old way of life, pre-metamorphosis, never to return), Gregor recalls his family with “love and tenderness,” and draws a last breath (110), leaving a corpse “completely flat and dry” (112).2

And then, there is a “new order,” “new humility” in the household, fearful of being cut off from their leader by Gregor’s father, who is accruing power, the lodgers depart (a second wave of departures for this transforming org), the charwoman begs off, Gregor’s parents and sister write to their employers to request a day of rest (as they finally acknowledge and collectively mourn the loss of Gregor), attaining as they do a new “equanimity” (114). On the train heading from city to countryside, Gregor’s family find their “future prospects” to be “not bad at all, for all three of their positions — something they had never before properly discussed — were in fact quite advantageous and above all offered promising opportunities for advancement” (117).

Whaaaaaat??? Admittedly my training was more in the exultant literary tradition of joyously joining writers like Walt Whitman, Herman Melville, and Henry James than the isolating, modernist alienation for which Franz Kafka is known.3 But every time I read “The Metamorphosis” I’m surprised by the metaphorical sunlight (e.g., “new dreams and good intentions”) breaking through clouds at the close of this familiar tale.4

Gregor: changed by work and not changing back. Those around him: changed in response to Gregor’s changes. In chronicling the increasing clarity and intention of the protagonist and supporting characters, The Metamorphosis has proved developmental in nature; in the end, more maturation than magic.

Such an odd and timeless tale, so old, and yet timely for leaders in my practice. For them, I’ll close the last Close Leaders on Kafka (for now!) with the arresting last lines of Stanley Kunitz’s poem “The Layers,” an ur-text of Nested Leadership:5

Though I lack the art to decipher it, no doubt the next chapter in my book of transformations is already written. I am not done with my changes.

Not to mention the poetry of Walt Whitman, from whence that phrase derived! I was fortunate to lecture on Whitman as a teaching assistant at Northwestern University.

Echoes of the CEO who proclaimed himself a “dry husk of a man,” see Close Leaders #13.

A former academic, I love the “Squeeze of The Hand” Chapter (XCIV) of Moby-Dick even as I feel endless gratitude to have narrowly evaded a career teaching it to 19-year-olds.

Close leading alongside thought leader on Leading with Wisdom & Compassion, Annie Perrin, has primed me to welcome these “new beginnings,” which as Annie reminds us she was taught in her extensive study on spiritual leadership, “do not arrive with trumpets.”

“The Layers,” is well worth reading and re-reading in its entirety, with its Gregor-like claim, “I am not who I was,” and plaintive refrain about love and loss in the face of change:

Oh, I have made myself a tribe out of my true affections, and my tribe is scattered! How shall the heart be reconciled to its feast of losses?

The Collected Poems of Stanley Kunitz (1978)